Colonial Currency

Before the American War for Independence, few coins were minted in the colonies. and often foreign coins like the Spanish dollar or Dutch "wampum" were widely circulated. Even though Colonial governments issued paper money to foster economic activity, the British Parliament passed a number of colonial "currency acts" to regulate the colonial economy.

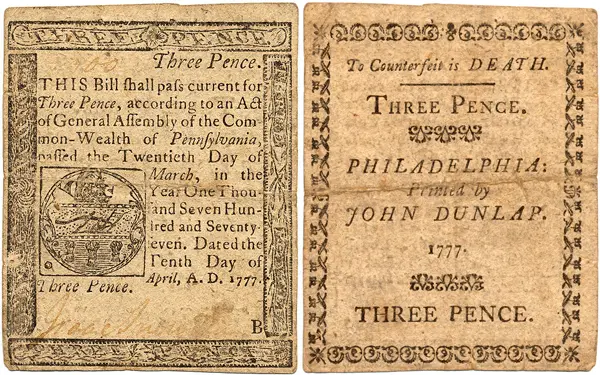

Front and Back of a Colonial Bill worth three pence

The colonists, to avoid British control, learned quickly how to barter for goods without specie (precious metals). Commodities like tobacco, animal skins, and dried fish allowed the colonists to trade for services without needing gold or silver. Yet, as the colonies grew in population, it became obvious that a standard form of currency was needed. The first illegal colonial mint was established in Boston, Massachusetts in 1652. It would become the first of many.

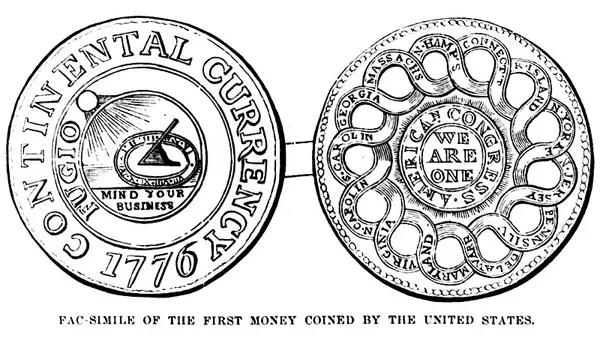

The Declaration of Independence officially freed the colonies from British monetary regulations, and they began to issue paper money, called Continental Currency, to pay for rapidly growing military expenses. Unfortunately, as there was nothing to back this currency, it became worthless by the end of the war.

To address these and other problems, the United States Constitution, ratified in 1788, denied individual states the right to coin and print money. The First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791, and the Coinage Act of 1792, established the first official United States Mint began the era of a national American currency.

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Share-Alike License 3.0